Banker's Digest

2025.08

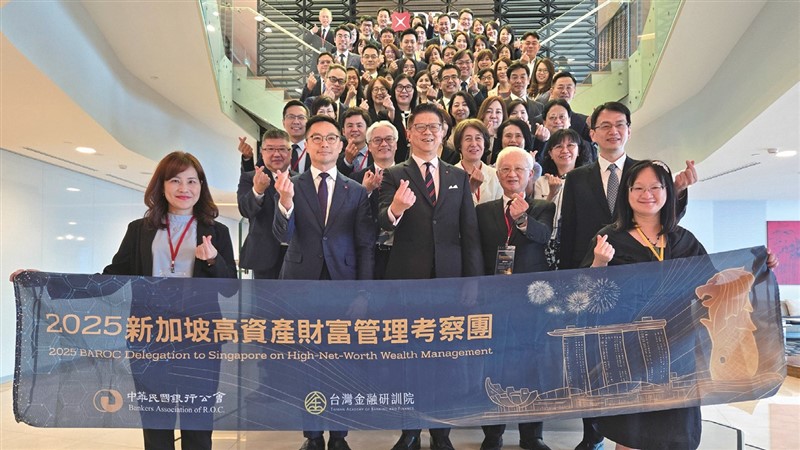

Singapore can provide models for Taiwan's Asian asset hub

To accelerate the development of Taiwan’s banking industry and cultivate talent on its journey to become an Asian asset management hub, the Bankers Association of the Republic of China (BAROC) visited the international financial center and Asian asset management hub of Singapore from July 6-10, 2025. Led by BAROC Chairman Dong Ruibin, the 2025 Singapore High-Asset Wealth Management Study Tour attended a learning session at the Wealth Management Institute (WMI), and visited DBS Bank, Raffles Family Office, and a leading global alternative asset management firm. These on-site exchanges gave it a deeper understanding of how Singapore has built its comprehensive asset management ecosystem, as well as the positioning and strategies of the financial institutions within it. Comprised of 59 members, the delegation engaged in extensive discussions on various topics during the visit, including family offices, private equity, and digital assets. The tour received enthusiastic support from senior wealth management executives at 18 financial holding companies and banks, including three chairpersons. It also received significant government attention. The Banking Bureau of the Financial Supervisory Commission sent Director Chen-Chang Tong, and nine senior representatives attended from the central bank and Ministry of Finance. Singapore has a long history in wealth management. Founded in 2003 with the assistance of Ho Ching at Tamasek and Peter Ng Kok Song at the Government Investment Corporation (GIC), the WMI provides practical, hands-on training to practitioners in wealth management, asset management, and regulatory compliance, laying a solid foundation for Singapore’s family office workforce. For a long time, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) has offered tax incentives to attract investment such as Sections 13R, 13X, and 13CA, and starting in 2022, it further introduced Sections 13D, 130, and 13U. Despite policy tightening and turmoil surrounding money laundering, family offices have experienced a resurgence since 2025. The review period for tax incentives been shortened, and private banks are also expediting the account opening process. Table 1: Regulations for Singapore family offices Section 13D Section 13O Section 13U MAS Approval Not required Required Required Funds jurisdiction Overseas Singapore Overseas or Singapore Applicable fund (company) type Overseas company, trust, or individual Singapore company or limited partnership (LP) fund Singapore or overseas company, trust, LP, or management account Location of management office Singapore Singapore Singapore Minimum management staff 1 2, including at least 1 non-family 3, including at least 1 non-family Minimum fees N/A 1. AUM < S$ 50M, S$ 200,000/year 2. S$ 50M ≤ AUM < S$ 100M, S$500,000/year 3. AUM ≥ S$100M, S$ 1M/year Capital deployment N/A Minimum of 10% of AUM or S$10 million Source: MAS When companies select a region for asset management, they typically consider several factors. 1. Political stability: are national policies consistent and sustainable, can they be maintained for extended periods without significant changes, and are they free from external threats? 2. Ease of doing business: are the business environment and tax conditions competitive and suitable for the company’s needs? 3. Labor costs: are there sufficient high-quality workers available at reasonable salary levels? 4. Infrastructure: are electricity, ports, and transportation facilities accessible to facilitate the smooth flow of goods? 5. Cultural compatibility: companies prefer to be based in regions which match their cultural background, facilitating smooth collaboration; and 6. English fluency: large multinationals traditionally communicate in English and therefore prefer to be based in English-speaking countries. Therefore, considering these factors, business and tax conditions are only one, albeit relatively important component for asset management centers and family offices. Success also requires comprehensive integration of many factors. Singapore’s family office operations and tax incentive models fall into two main categories: overseas investment holdings (13D) and local enterprise developments (130/U). In recent years, due to the Common Reporting Standard (CRS), many multinational corporations have been unable to be deemed to be conducting substantial business operations in tax havens. Consequently, the search for “economic substance” has become critical. Since the 13D and 130/U models are designed for companies operating offshore and domestically, respectively, establishing a family foundation in Singapore under 13D does not require MAS approval, while the 130/U model requires an approval process of approximately three months. Regarding tax-exempt “incentivized funds,” third parties other than family members are still not allowed to participate in the principal (equity) portion, but family members can serve as investment professionals for family offices, with minimum local management fee requirements set based on asset size. Investment targets are restricted to local real estate (including REITs) and cryptocurrencies. Illegal investments may incur punitive stamp duties of up to 40%. Family investment professionals must be at least 18 years old and must complete the necessary documentation to apply for a work visa from the Employment and Labour Department. The minimum monthly salary is approximately S$3,500, depending on the individual’s age and educational background; the higher the applicant’s educational background, the lower the threshold. This is primarily due to the government’s desire to attract high-level talent to Singapore to add to the local professional workforce. Therefore, family office investment professionals can obtain Singapore Permanent Residency (PR) in approximately 12 months, compared to the 3-5 years typically required for ordinary professionals. However, the Singapore Immigration and Checkpoints Authority (ICA) takes applicants’ news reports and social media profiles very seriously: negative news or inappropriate information online may result in ineligibility. Singapore offers various tax incentives (around 5-15%) and terms (usually 3-5 years, with extensions available) for the establishment of global trade centers, regional/global management headquarters, financial coordination centers, and R&D centers. The latter are particularly special: since they often lose money in the early stages, the government provides a deduction of up to 250% of losses against future taxes. Furthermore, family offices have bilateral tax treaties with over 90 countries, although currently not including the US. If any member of the family foundation is a US citizen, the entire structure becomes complicated and may be rejected. Tax advisors typically recommend establishing separate trusts for US-based clients, rather than including assets in the family foundation. Furthermore, single-family offices, which typically have fewer employees, have recently adopted an external asset management (EAM) model. These agreements involve signing a limited power of attorney (LPA) agreement with an external family office or professional investment institution, allowing the external entity to manage the client assets while the bank provides custody services. This practice is similar to the discretionary mandate offered by investment trusts and investment advisory firms in Taiwan, although Taiwan’s licensing requirements differ slightly from those in Singapore and Hong Kong. In January, the Singapore government announced preferential measures for the Johor-Singapore Special Economic Zone (JSEZ), including a 10-year, renewable 5% corporate tax rate for Singapore-based companies operating in specialty chemicals manufacturing, aerospace, AI/quantum computing, pharmaceuticals, and integrated tourism in the Zone. This will encourage high-end businesses to establish management centers in Singapore and manufacturing centers in Johor, increasing labor supply while reducing operating costs, while also reducing the workload at the crowded Singapore-Malaysia border. Asset allocation has always been a key focus of asset management. With the addition of private equity (PE), the allocation ratio has shifted from 60% stocks and 40% bonds to 40% stocks, 25% bonds, and 35% private equity. Profitability is the primary motivation for this change. The global PE market currently has approximately $1.2 trillion in assets, including $320 billion in real estate, $389 billion in debt and insurance, $371 billion in PE, and $88 billion in other diversified asset structures. Equity investments are primarily in startups and M&A, while debt investments primarily focus on direct lending, mezzanine financing, distressed debt acquisition, and special situation lending; and real asset investments focus on core and opportunistic real estate and infrastructure. Looking at the PE market, the annualized return (15.1%) and volatility (9.9%) both outperform the public equity market (8.1% annualized return at 16.7% volatility), demonstrating that the recent boom is well-founded. The biggest drawback is however liquidity. Investment periods often range from 5-8 years, with specific redemption periods. Missing one period may mean waiting for the next, making it challenging for investors to determine the timing of entrance and exit. To expand market share, therefore, some PE firms are introducing semi-liquid or interval products, meaning they can be redeemed at set intervals. Allocating funds to meet the liquidity needs of a small number of clients can lead to mismatches in investment timing, however, which affects overall returns. The United States has the most open regulatory framework for PE, with four client tiers based on asset size: three federal and one state tier (with total assets of $700,000 and an annual salary of $70,000). The lowest state tier has the highest fees and regular reporting requirements, as well as the highest expense ratios. Some private bond funds are required to disclose their net asset value daily. Japan, on the other hand, has relaxed the asset threshold for qualified investors from $2 million to $1 million, and is further promoting public offerings of alternative investment products. Crypto assets have recently become a more important asset allocation option for high-net-worth individuals (HNWI), particularly younger HNWI from wealthy families. Consequently, some financial institutions have already entered crypto asset trading, establishing exchanges. Initially, they focused on highly liquid currencies like Bitcoin, but they have gradually expanded to include digital asset transactions, asset tokenization, stablecoins, and virtual asset custody and settlement. DBS’s DBS Digital Exchange (DDEx), established in December 2020, is the first digital asset exchange backed by a traditional bank. The entry of banks into cryptocurrency through digital exchanges is a pioneering move, but the main participants are bank clients, for whom rigorous know-your-customer (KYC) procedures may limit trading volume. Nevertheless, as more HNWI clients become familiar with crypto assets, digital exchanges backed by banks may experience rapid growth, gradually gaining favor for their stable account connectivity and reliable security. However, the majority of cryptocurrency trading still takes place on dedicated decentralized exchanges. Asset managers have capitalized on international tax reforms, and funds are flowing from tax havens into countries with familiar and tax-friendly rates. Furthermore, Taiwan’s recent special law for repatriating overseas funds has also attracted NT$335.1 billion in capital inflows. Taiwanese businesses have accumulated significant amounts of capital overseas, with much of it likely remaining overseas. Will that capital wait for opportunities to return, or will it remain overseas permanently? Wherever this capital resides, investment opportunities, inheritance methods, and tax burdens will all likely be key considerations. Singapore’s experience shows that an approach similar to 13D would be the most promising first step to attract capital back onshore. Other approaches, such as 130/U, may affect clients’ current tax planning and require careful consideration within applicable industry categories. Therefore, the government must carefully consider what types of capital it seeks to attract. The author is Director of the Communication Department of the Financial Inclusion Group of TABF.