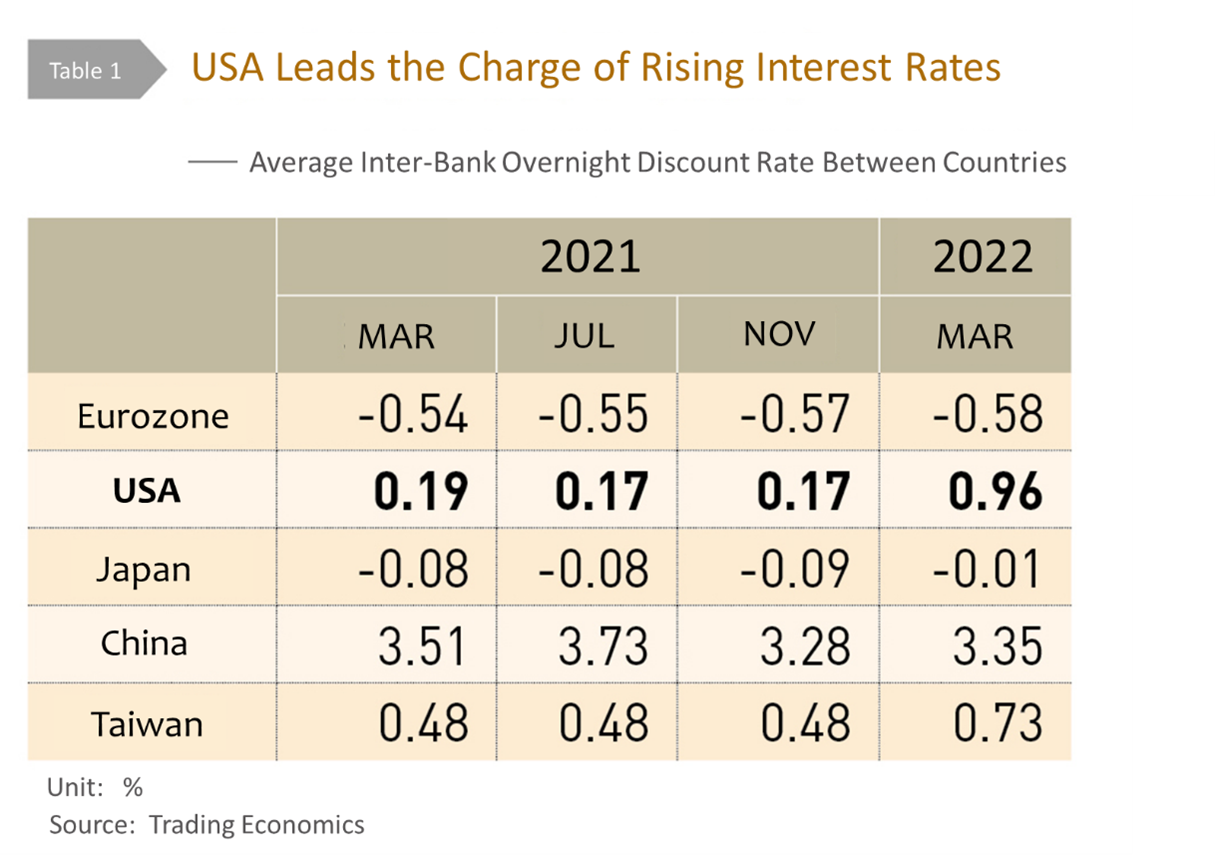

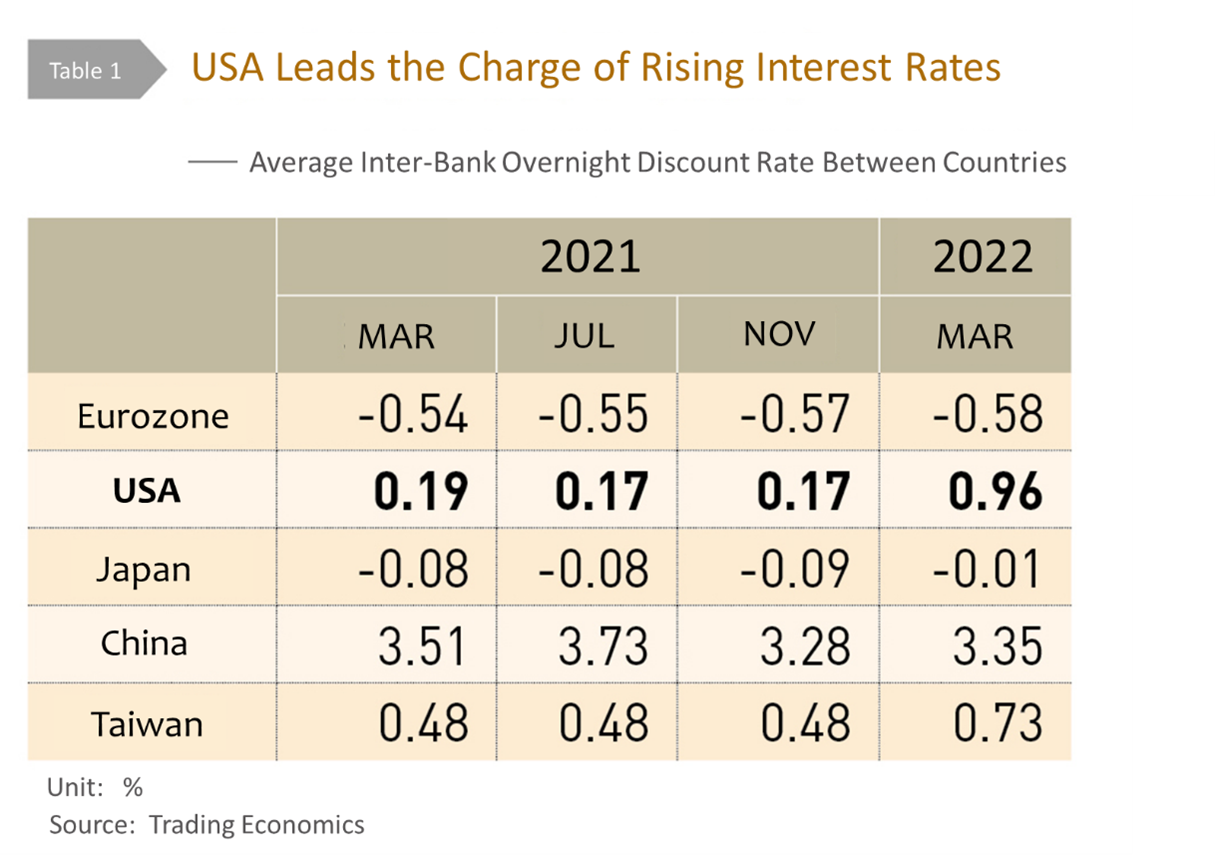

Inflation now exceeds 7% in Europe, 8% in the United States, 5.1% in the eurozone, and 5.5% in the UK, setting record highs since the energy crisis in the early 1980s, and causing public resentment. With overall employment figures slightly improved, the market has reached a consensus that the Federal Open Market Committee of the Federal Reserve will gradually increase the target range of the benchmark average overnight lending rate in the first half of 2022. Fearing a possible economic recession caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it began to act in late March. Table 1 lists the average overnight lending rates among various central banks. The US has led global tightening, and the Bank of England and European Central Bank are expected to follow close behind. Weighing the pros and cons, the monetary policy objectives of the US and Europe will be slightly downgraded in light of the risk of stagflation following the war, as both show determination to control inflation. The US dollar, euro and pound sterling are the most important international reserves and trading currencies, and no financial market can avoid the impact of quantitative tightening by these respective central banks.

Will China and Japan tighten?

The current monetary policy trends in Asia's two largest economies is quite different from in European and the US. In 2021, the People's Bank of China started accelerating its push towards easing, while the Bank of Japan has been buying bonds to support the market and drive down yields, and been firmer in its quantitative easing. The two central banks have their own reasoning. China's economy is facing the most significant recession in the 40 years since reforming and opening up began. Further, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has created geopolitical risks. At least as far as the consumer price index is concerned, however, inflation seems to be under control (1.5% as of February 2022). Even though Japan has exited long-term deflation, for its part, its inflation rate (0.5% in February) is still lower than the 2% target of the Bank of Japan, which supports the rationality of the loose monetary policy position.

The policy direction of Europe and the US will certainly affect the thinking of the two major central banks in Asia. The Fed has said in various statements that it will take a more active attitude towards inflation, leading to a sell-off in the bond market and a rapid expansion of the gap between long-term and short-term interest rates. This has not only brought upward yield pressure of European government bonds, but also on Japanese government bonds. In mid-February 2022, the highest yield of 10-year Japanese government bonds had risen to 0.23%, the highest since 2016, which is also close to the implied ceiling set by the Bank of Japan. The Bank of Japan had to intervene to ensure that the yield of its 10-year benchmark bond remained within the limit of 0.25%. Meanwhile, the same-day yield spread between China's three-year central government bonds and US Treasury bonds has shrunk from a high of about 3% to the current 0.5%. Such a tight spread does not reflect the gap between the credit risks of the two countries (the United States is AA+, while Japan and China are A+ in S&P's long-term sovereign risk ratings. For US domestic corporate bonds, the default risk premium between AAA and AA was about 0.8% in February, 2022), which does not augur well for China as it hopes to continue attracting foreign investment. In particular, fixed income assets accounted for 60% of its total international investment in 2021.

Rising corporate financing costs in China and Japan

The increasing interest rates in Europe and the US may be a light at the end of the tunnel for China’s current account. China’s trade surplus is expected to continue shrinking in 2022, and its low interest rate will ensure that the RMB continues to weaken relative to other international currencies, which will help boost exports and make up for the slowdown in investment inflows in the international financial account on China’s capital supply. After all, Beijing is not happy to see major international economies applying the emergency brakes, which has a negative spillover effect on its already weak economic growth.

The impact on private enterprises will however be uneven. Since Japan ($1.3 trillion) and China ($1.5 trillion) are the largest net creditors of debt issued by the US treasury, the strengthening of the US dollar and increase of interest rates will have a wealth effect for both nations. For firms in these countries, however, there is a great demand for USD-based financing on the international market. Their borrowing costs will rise with the Fed’s monetary tightening policy, and corporate financing costs will get even higher with the subsequent appreciation of the US dollar.

Reduced household disposable income inhibits growth

China’s main problems with the rise in US bond interest rates are the cost of USD denominated corporate debt and the increased risk to banks in developing countries. For Japan, the reduction of household disposable income will inhibit growth. By the end of 2021, the top 100 financial institutions in the world, which include 22 Chinese commercial banks (all state-owned) and nine Japanese banks, with total assets of about US$ 2.75 trillion and US$ 1.11 trillion respectively, held a large amount of USD-denominated debt. After the pandemic, a considerable number of loans in developing countries have proven unsustainable.

Particularly with emerging market lending derived from the Belt and Road initiative, the transparency of investment and corporate governance in China is worse than those in other countries. This is not good news for China's economy, which is discovering the cyclical nature of the business cycle and experiencing a growth slowdown caused by structural change. The treasury bond yield control strategy of the Bank of Japan will weaken the yen even further. Although it may help increase the competitiveness of foreign exports and end the long-term low inflation rate, it will also reduce Japanese household purchasing power, and the wages of office workers are unlikely to catch up with rising prices.

Lingering pressure to raise rates in the medium term

The probability of global stagflation has increased significantly following the outbreak of the Ukraine war. It is difficult for China and Japan to stay outside of this trend, and it has become more likely that they will adjust their monetary and financial policies. Ukraine and Russia are major global food and energy producers, accounting for 30% of global wheat exports. Russia is the world's third largest crude oil producer and second largest exporter, second largest wheat exporter, and most important natural gas supplier to Europe. Its exports account for 8% of the world supply, and its various metal minerals and timber are also very substantial. Ukraine, known as the granary of Europe, is the world's third-largest exporter of wheat, largest producer of sunflowers, and one of the important producers of rare earths. Due to the unprecedented economic sanctions imposed by Europe, the US and Asian democracies (except India) on Russia (including on oligarchs, international trade, international finance, tourism, and a high-tech and semiconductor embargo), global supply chains are restructuring fast. The world's major oil companies have refused to refine Russian oil, and have even withdrawn their investments in the country, causing international crude oil prices to soar to a 14-year high.

With the interruption of grain transportation and rise of global grain, transportation and fertilizer prices, food prices have begun to soar. One month after the outbreak of the war, international food prices exceeded the level when the Arab Spring broke out in 2011; the price of staples is more than twice that of the previous year. Both China and Japan need to import a large amount of oil and metals. Before the war, China relied on wheat and corn imports from Ukraine and Russia, and even rented land for cultivation in Ukraine. All these factors underpin medium and long-term price movements around the world. From this perspective, China and Japan will be under pressure to raise rates in the medium term.

Monetary policy will change from divergence to coherence

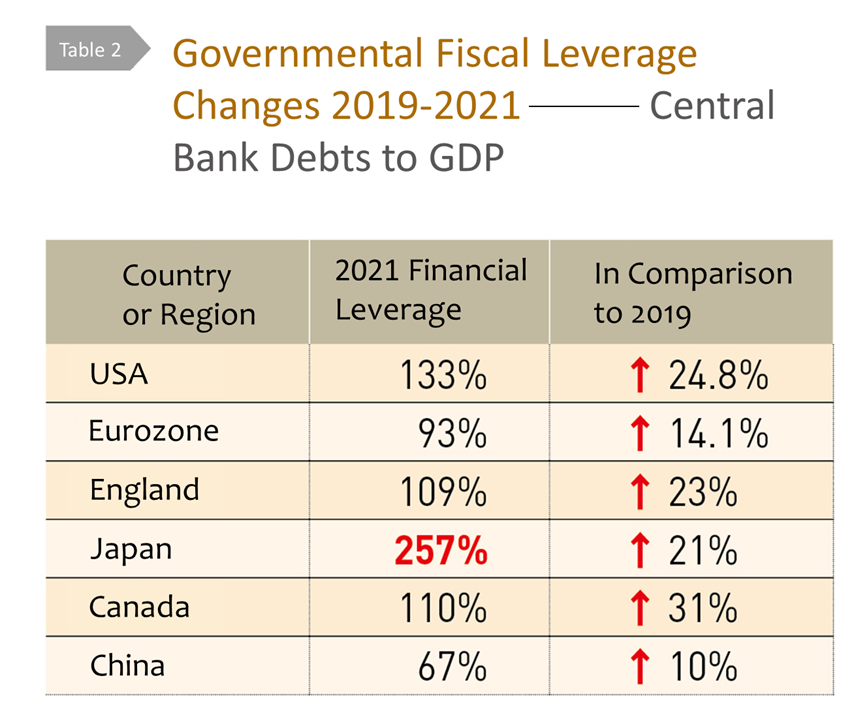

Since the second half of 2021, the divergence of monetary policy between the West and Asia has widened as European and US central banks have raised interest rates and tightened their money supply. It will be difficult for the central banks of China and Japan not to follow suit. The main reason is that since 2020, governments around the world have generally used debt to cover stimulus to save the economy from the pandemic. Measured by percentage of gross national product (GDP), comparing 2019 to 2021, government financial leverage of the United States increased by 24.8% (133% at the end of 2021), the eurozone by 14.1% (93% at the end of 2021), the UK by 23% (109% at the end of 2021), Japan by 21% (257% at the end of 2021, ranking first among developed countries), Canada by 31% (110% at the end of 2021), and even China by 10% (67% at the end of 2021) (see Table 2).

In the case of the US, the balance of federal government debt reached US$ 2.84 trillion by the end of December 2021, while the total government debt of the European Union in the same period was €1.180 trillion (about US$ 1.35 trillion). With this record-breaking government debt, coupled with the global shortage of food and energy caused by the war, not to mention the impact of debt default risk of the Russian Federation on the global financial market, central banks must think about coordination. Otherwise, international financial market risk could get out of control, resulting in a sharp increase in rates and increased interest expenditure, depleting governments’ limited budgets. This will significantly increase the risk of broader sovereign default.

(The author is a professor of Finance at Northeastern University)