After Russia invaded Ukraine in late February 2022, an international consensus quickly formed and a number of economic and financial sanctions were imposed on Russia. Two of the financial sanctions attracted the most attention. The first was the decision on February 26 of the US, Britain, Canada, and EU (later joined by Japan and South Korea) to expel some Russian banks from SWIFT, the system responsible for information transmission in the international payment system. Second, on February 28, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) of the US Treasury Department announced a ban on transactions with the Central Bank of Russia, the National Wealth Fund, and Russian Ministry of Finance, leading many other countries to follow suit.

This article focuses on the sanctions against the central bank, which is a distinctive sanction strategy. As a “bank of banks,” a country's central bank is its most important official institution to maintain financial stability. In the case of financial crises, it is the liquidity provider of last result in the financial system. The unprecedentedly coordinated sanctions against Russia’s central bank have paralyzed its ability to support the ruble and cut off all channels for it to use its foreign exchange reserves. President Elvira Nabiullina of the Central Bank admitted that when the ruble fell 33% against the dollar on February 28, its foreign reserves were not liquid enough to buy rubles in order to prevent it from depreciating significantly. As a result, the central bank asked exporters to sell most of their foreign currency holdings, imposed capital controls, and sharply raised the policy rate to 20% from 9.5% to curb capital outflows. However, the ruble continued to depreciate heavily, reaching 70% on March 7.

A run on the ruble

On March 1, the central bank ordered that no interest be paid to foreign investors holding medium- and long-term treasury bonds, and they were not allowed to sell their bonds – a semi-technical default. The shortage of foreign exchange has made international investors highly suspicious of Russia's solvency. Figure 1 shows that 5-year bond CDS spreads soared to 4,156 basis points on March 11, far exceeding the 1,084 basis points in 2008, indicating that the probability of default on Russian public debt has skyrocketed. In addition, the central bank could not provide banks with their foreign currency needs or assist companies to make or receive payments in foreign currency. This sparked anticipation of cash shortages and payment disruptions, as well as a scramble to withdraw deposits and exchange them for foreign currency, leading to bank runs across Russia. Generalized panic in the Russian financial system intensified.

The Economist (March 5) even called this brewing financial panic the fourth financial crisis in Russia in 25 years – the first three being the 1998 Russian crisis, 2008-2009 global financial crisis, and 2014-2016 Russian financial crisis. The four crises over the past 25 years have all more or less been related to Russia’s invasions of neighboring countries.

After being sanctioned for annexing Crimea in 2014, Russia tried to build a firewall to reduce losses from possible future sanctions. The central bank accumulated foreign exchange reserves, sold dollar bonds, and increased its reserves in different currencies to diversify its investment portfolio risk and partially “de-dollarize.” At the same time, it purchased gold in large quantities and stored it within Russia. Moscow’s increase in renminbi and euro reserves is especially important, mainly because China is Russia’s ally and Europe is quite dependent on its oil, natural gas and other commodities. In addition, Russia diversified its foreign reserve currencies, and also distributed the reserves to more locations to prevent them from being frozen. At the same time, it also developed the System for Transfer of Financial Messages (SPFS, 2014) system to replace SWIFT.

Russia’s foreign exchange and gold reserves are quite large and its asset portfolio has changed significantly in recent years as it has built closer contacts with other central banks and international institutions. It is therefore worth observing how these changes will affect the effectiveness of these sanctions on Russia, as well as how central banks will manage their foreign exchange reserves and gold.

Foreign exchange reserves and gold

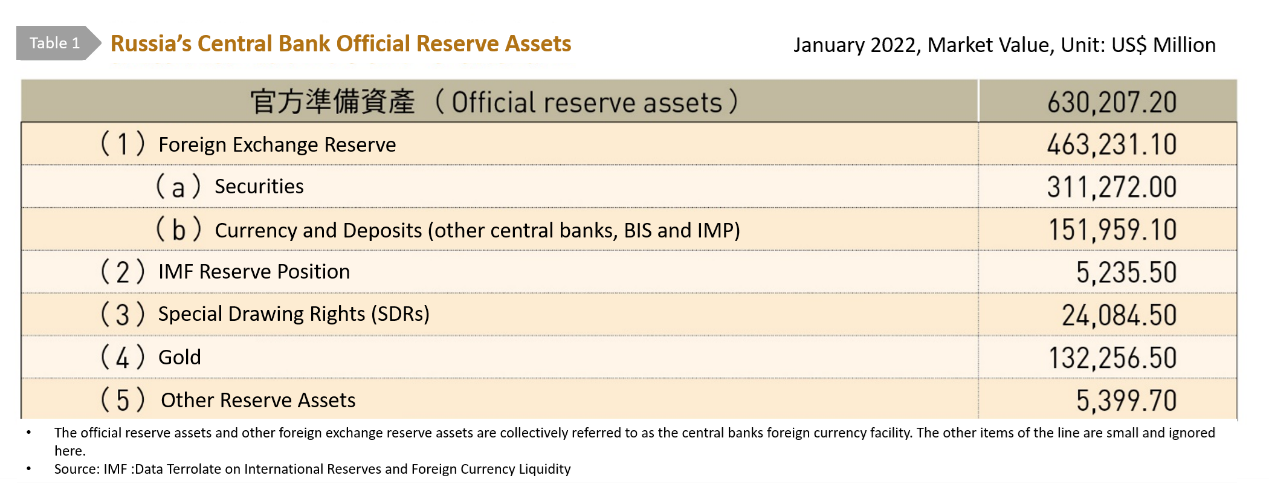

Table 1 shows that the Central Bank of Russia held US$ 630.2 billion in official reserve assets (or international reserves) at the end of January 2022, including US$ 4.632 trillion of foreign exchange reserves (mainly held in securities and cash and deposits), US$ 132.2 billion in gold, and $29.3 billion in Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) at the IMF. Since foreign exchange reserves and gold are the two most important items, the following discussion will focus on these two items.

Figure 2 shows changes in Russia’s foreign exchange and gold reserves over time. First, looking at the changes before and after the 1998 crisis, the 1994 invasion of Chechnya was financially counterproductive. When the 1997 Asian financial crisis caused the price of oil and raw materials to plummet, Russia's export revenues fell sharply, creating chaotic domestic politics, and resulting in a serious financial crisis and a devalued ruble. In August 1998, the central bank announced a default on domestic debts and suspended repayment of principal and interest on foreign debt. In order to slow the fall of the ruble, it almost exhausted its foreign exchange reserves from about US$ 20 billion to US$ 6.6 billion, but the ruble still depreciated by 75%.

Since 2003, oil prices have risen sharply, from US$ 25 per barrel to US$ 145 per barrel in June 2008. Russia's crude oil revenue has increased rapidly, and foreign exchange reserves have increased rapidly. During the Olympics in August 2008, Russia invaded the Republic of Georgia to prevent it from joining NATO. Soon after the global financial crisis broke out, in order to defend the ruble and prevent foreign capital flight, the central bank implemented various stabilization costing more than US$ 200 billion, and foreign exchange reserves dropped sharply from about US$ 582 billion to US$ 367 billion, but the ruble still depreciated by about 35%.

In 2014, economic sanctions were imposed on Russia following its annexation of Crimea and a conflict with Ukraine in Donbas. At the same time, from mid-2014 to the beginning of 2016, due to a large increase in shale oil production in the US and international oversupply, the international price of crude oil dropped by nearly 70%, and Russia's export revenue was hit hard. As a result, a financial crisis broke out. Funds fled in panic, and the exchange rate plummeted by about 50%. The cost of the war, coupled with the central bank's support for the financial system and the ruble, again cost about US$ 160 billion in foreign exchange reserves. The economy stagnated, and severe inflation was also caused. The crisis lasted until 2016.

It is worth noting that the central bank bought gold in large quantities after the global financial crisis; since 2014, it has accelerated its accumulation. Gold inventories surged from 519.6 metric tons at the end of 2008 to 2,301.6 metric tons at the end of 2021, a growth rate of 343%; its market value increased from US$ 13.3 billion to US$ 133 billion. Interestingly, the People's Bank of China also bought gold significantly during the same period. Its stock rose from 600 to 1,948.3 metric tons, a growth rate of 228%. The two central banks’ increased gold purchases accounted for 55% of the increase in global official gold holdings between 2008 and 2021.

Changes in foreign reserve currencies and locations

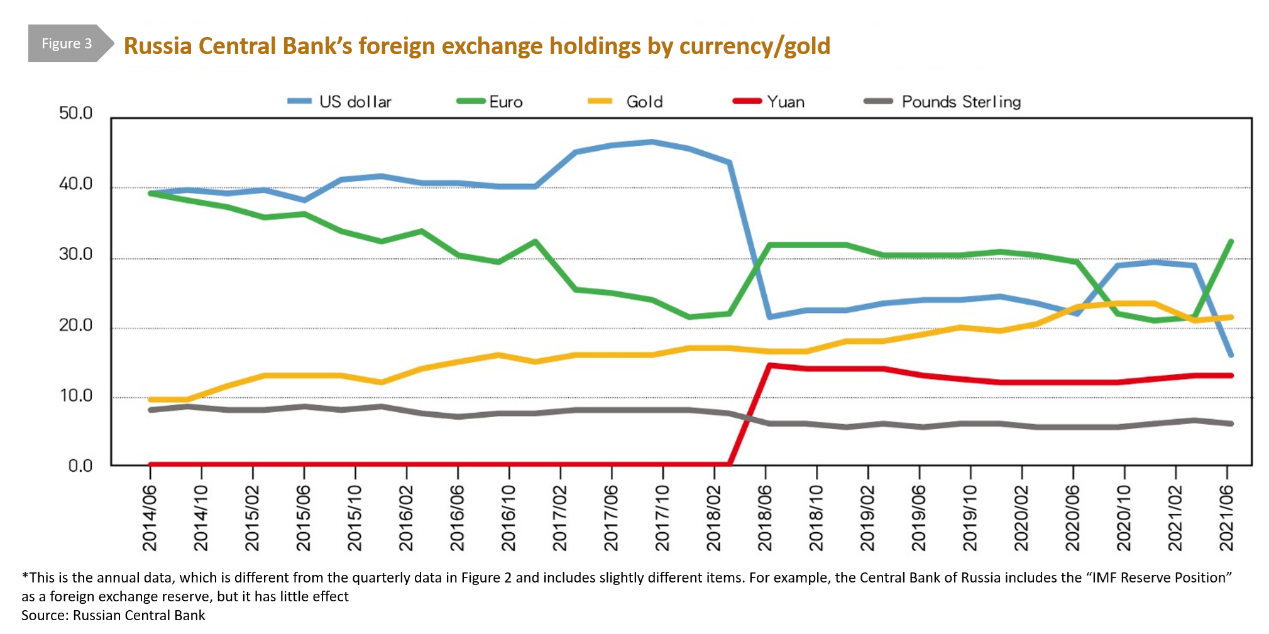

After Russia was sanctioned in 2014, it gradually adjusted the currency allocations of its foreign reserves to “de-dollarize.” Figure 3 shows that in the first stage from 2014, it gradually reduced its proportion of euros and switched to gold. The second stage from 2018 saw a major changes. Between March and May of that year, it sold off its holdings of US treasury bonds, and USD reserves and gold assets decreased from 43.7% to 21.8%. At the same time, it increased holdings of renminbi and euro assets; the proportion of renminbi assets rose sharply from only 0.1% to 14.7%.

The central bank’s stated purpose for selling dollars was to diversify its portfolio, but it was generally believed to be retaliation for the US sanctions over the past few years. Due to the sharp sell-off of US treasury bonds, the rate on 10-year treasuries exceeded 3%, but stabilized shortly after. In the final stage, the proportion of US dollar assets was further reduced to a new low of 16.4% (June 2021), and euro assets were increased in turn.

In recent years, Russia has not only diversified its foreign exchange holdings, but also transferred them to financial institutions in more countries. Figure 4 shows that the most significant change from June 2014 to June 2021 was a significant reduction in deposits in the US, moving to China and Japan. According to the June 2021 data, 13.8% of its foreign exchange and gold reserves were deposited in China, 6.6% in the US, 9.5% in Germany, 12.2% in France, 4.5% in the UK, 5% in international organizations, and 10% in Japan, with a miniscule amount is stored in Canada, Austria and other countries. The central bank holds 16.4% of its assets in US dollars, but only 6.6% in the US; at the same time, it only holds a small amount of yen assets, but 10% of its foreign exchange reserves are based in Japan. Interestingly, it stores all of its gold within its own borders, unlike many countries, which store it in underground vaults at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Bank of England.

The author would like to thank Li Rongqian, Counselor of the Central Bank and Professor Chen Xusheng of the Department of Economics of National Taiwan University for their valuable opinions. However, the content of this article represents personal opinions and has no relation to them or their positions. The author is solely responsible for any errors.