The content of this article represents the author’s personal opinions, and any errors are also the responsibility of the author.

The central bank is justified in stabilizing the housing market

Since loose monetary policy is one of the main reasons for rising housing prices, an active response can reduce the negative impacts of loose monetary policy: threats to financial stability, leading to resource misallocation and an increasingly unequal wealth distribution.

Threatening financial stability

By statute, the central bank is responsible for promoting financial stability, but the term is vague and has a wide range of implications, and cannot easily be represented with a single quantitative indicator. So what exactly does financial stability mean? In fact, regardless of whether a central bank’s objective includes stability, the key point is that there must be a set of clear and observable supervision indicators and policy tools to implement the objective, otherwise it will not be implemented. Recent international financial supervision reforms have given central banks more complete pre-event macroprudential indicators and policy tools and post-event crisis response tools.

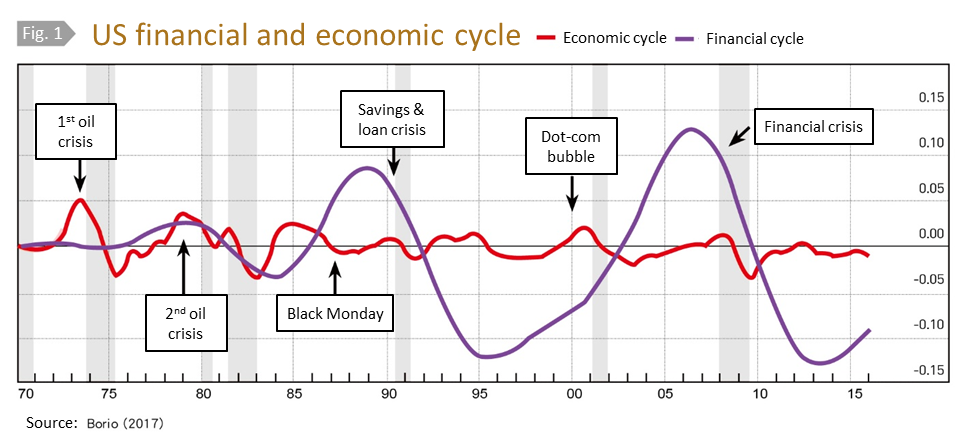

Regarding pre-event macroprudential supervision indicators for the real estate market, besides the growth rate and concentration of mortgage loans (since the NPL ratio is a backwards-looking indicator, it cannot be used as an early indicator), the trajectory of housing prices is another important indicator for financial stability. Many studies have shown that credit expansion is always accompanied by continuous and rapid growth in asset prices, as well as subsequent crises, which also leads to credit crunches and price crashes. This process is collectively referred to as the financial cycle. A large financial cycle increases systemic risk and threatens the stability of the financial system.

The important characteristics of a financial cycle include: (1) A cycle length and volatility that far exceed the economic cycle; (2) The peak of the financial cycle often coincides with the outbreak of a financial crisis; and (3) If a financial crisis involves a collapse in housing prices, it often causes a deeper recession and longer recovery. As shown in Figure 1, the length of the financial cycle in the United States is about 16 years, and it has lengthened by about 8 years. Cheng and Chen (2021) estimated that Taiwan's housing price cycle lasts about 5.8 to 6.6 years, which is much shorter than the housing price cycle of industrialized countries, but still longer than Taiwan's economic cycle (about 3.5 years).

These characteristics give rise to the following policy implications: (1) Since monetary policy significantly affects housing prices, it is one of the important drivers of Taiwan’s financial cycle. When the central bank performs its statutory duty to promote financial stability, this means responding to fluctuations in the financial cycle. (2) Since the financial cycle is longer than the economic cycle, financial fragility takes some time to become apparent. To maintain financial stability, the central bank needs to prepare before expectations of rising housing prices are formed to prevent the financial cycle from affecting the financial sector. (3) Since housing prices are a major component of the financial cycle, their cycle is critical for financial stability. Some think that housing prices are not the central bank's focus, and the central bank is concerned about financial stability, but it is clear a contradiction to stabilize finance but ignore housing.

Resource misallocation

As loose monetary policy causes real estate prices to rise, capital and labor may be diverted to related industries, thereby crowding out the resources available to other industries and causing misallocation. A continuous rise in housing prices affects resource allocation through the following channels: (1) Crowding out: Banks provide more funds to departments or companies with more land, crowding out other investments. (2) Speculation: Businesses buy more real estate, but reduce other non-land investments and innovation activities, which lowers overall economic investment, productivity and subsequent growth.

For example, in China, whose economy growth has long been driven by construction and real estate investment, the concentration of resources in related industries is quite clear. Chen et al. (2017) used the methodology of Hsieh and Klenow (2009) to estimate the resource misplacement caused by China's real estate market, finding that when prices rise by 100%, improper capital allocation reduces total factor productivity (TFP) by 26%. In addition, Borio et al. (2016) used data from 21 advanced economies to find that in the 10 years before and after the global financial crisis, due to the rapid expansion of credit, the labor force was directed to less productive sectors related to real estate, resulting in a cumulative productivity loss of 6%.

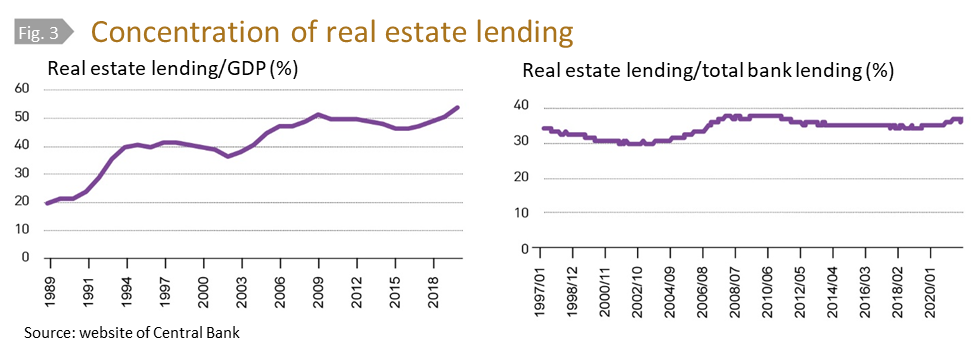

Using Taiwanese data, the growth rate of real estate loans (residential purchase + home repair + construction) has accelerated in recent years (Figure 2), and the concentration of real estate loans (proportion to GDP and to total bank lending) has also hit historical highs and continued to rise, indicating that resources are rapidly being concentrated in related industries. In addition, the number of home loans to domestic corporates has increased rapidly in the past one to two years, and house hoarding and short-term transactions have risen significantly. The use of corporate funds to buy real estate crowds out other non-land investment and innovation activities.

Chang Tien-Huei, Chu Hao Pang, and Chen Nankuang (2021) used Taiwanese data to estimate that sharply increasing housing prices have the following long-term effects: (1) A negative (but insignificant) impact on overall economic output, investment and TFP, and a significant negative impact on jobs; and (2) A significant negative impact on output, investment, employment and TFP in the manufacturing industry.

Excessive concentration of resources in real estate not only leads to misplacement of resources and drags down long-term productivity and economic growth, but also encourages cycles of housing price inflation and contraction, increases systemic risks, and threatens the stability of the financial system. Therefore, rising real estate prices have led to misplacement of resources and reduced long-term productivity, which are also some of the negative effects of loose monetary policy.

Deteriorating wealth gap

Since the early 1980s, the wealth gaps in many advanced countries have increased (Atkinson, 2015; Piketty, 2014). Domanski et al. (2016) used data from a household survey of six advanced economies over the past 20 years to show that stocks and real estate are the most important drivers of income and wealth inequality. Since monetary policy is one of the main drivers of asset prices, whether monetary policy is worsening inequality, and whether the central bank should take responsibility, have been hotly debated.

The traditional view is that the redistributive effect of monetary policy may be offset in the economic cycle, so it is roughly negligible. For example, Bernanke (2015) believes that in the long run, monetary policy is neutral or almost so, so its long-term effect on income and wealth distribution is limited. However, after the global financial crisis, long-term low interest rates coupled with non-traditional monetary policies such as quantitative easing may have produced significant redistributive effects and worsened wealth inequality. Especially since 2009, civic movements such as “End the Fed,” “Occupy Wall Street,” and “Positive Money” have all urged the central bank to take into account long-term issues such as inequality and climate change.

Although distribution and inequality are beyond the responsibilities of central banks, many central banks are starting to pay attention to these issues. According to statistics from BIS (2021), less than 0.5% of central bank speeches mentioned distribution and inequality in 2009, but this has risen to 9% in 2021. As the central bank is involved in a wide range of fields, others have recently called for the central bank to stop expanding its focus to income and wealth inequality or climate change, so as not to get involved in quasi-fiscal or political issues. However, if the inequality of income and wealth worsens, is it not to some extent the consequence of long-term monetary policy?

Recently, researchers have analyzed the redistributory effect of monetary policy and its impact on income and wealth inequality in the context of household heterogeneity, finding that it may indeed significantly affect both income and wealth distribution through different channels: (1) Savings redistribution: lower interest rates are good for net borrowers but bad for net lenders; (2) Disinflation expectations: loose monetary policy leads to unexpected increases in inflation, which benefits net borrowers but harms net lenders; (3) Income composition: Monetary policy has different effects on the income compositions of different households. If loose policy makes investment income and profits grow faster than labor wages, income distribution will further deteriorate; (4) Salary heterogeneity: Monetary policy has different impacts on labor wages in different sectors, which affects income distribution; (5) Asset portfolios: Loose monetary policy pushes up the prices of assets, which affects household balance sheets through differences in asset portfolios.

The transmission channels that affect income will eventually affect the distribution of wealth, and changes in housing prices directly affect the distribution of wealth through the asset portfolio channel. If housing ownership is concentrated at the top of wealth distribution, rising housing prices will aggravate wealth inequality; if ownership is widely distributed among the population, wealth inequality may decrease.

Empirical findings on the impact of monetary policy (traditional and non-traditional) on income and wealth inequality have depended on the strength different transmission channels in different countries. Some studies in the US, the Eurozone and other regions have found that the impact of rising housing prices is insignificant, or even slightly improves the wealth distribution. The main reason is that a higher proportion of housing wealth in these regions is distributed at the lower-to-mid-end.

Based on this inference, if a country’s housing wealth is not concentrated at the lower-to-mid end of the distribution, then rising prices will easily cause the distribution to deteriorate. According to Saez and Zucman (2016), the top 1% of the US account for only about 10% of total real estate wealth. In contrast, that ratio in Taiwan increased from 58% in 2004 to 69% in 2014, which is close to the 75% of households for which housing accounts for 50% to 90% of total wealth (Hsien-Ming Lien et al. (2020)). Therefore, rising housing prices are more likely to lead to a deterioration in wealth distribution in Taiwan than in the US.

Therefore, although the problem of worsening unequal distribution is not within the scope of central bank statutory responsibilities, it may be one of the consequences of its long-term loose policies, via housing prices. Therefore, it is an important issue which cannot be avoided.

Tools for housing price stabilization

What policy tools does the central bank have to respond to changes in housing prices? Should it use monetary policy (interest rates) to respond to the financial risks of asset price fluctuations – that is, to “lean against the wind” (LAW)? This debate has been ongoing for decades.

The discussion on this topic can be roughly divided into two stages. In the first stage, which lasted until the global financial crisis, the mainstream view was that monetary policy should only respond to asset prices when they affect inflation expectations. In the second stage, following the crisis, the focus has shifted to the most effective way to resolve asset price bubbles driven by credit expansion. Svensson (2017) used Sweden’s experience of raising interest rates to curb housing prices to argue that LAW is a blunt policy. Interest rate policies used to affect the business cycle are not a good choice for financial sector problems; macroprudential policies and tools are more effective. Studies such as IMF (2013, 2015), Martinez-Miera and Repullo (2019), and Kuttner (2013) share similar conclusions with many central bank officials.

However, others believe that the use of monetary policy to respond to asset price deviations effectively reduces the probability and severity of future financial crises, and prevents the overall economy from falling into deep and long recessions. For example, Stein (2013) argued that if the economic environment strongly encourages financial institutions to use regulatory arbitrage and assume higher credit risks to earn returns, macroprudential tools cannot contain this threat. In contrast, an important advantage of monetary policy is that it “gets in all the cracks.” Gourio et al. (2018) found that when financial shocks affect the probability of a financial crisis, interest rate policy is the most systematic response to the growth of credit, because the increase in welfare brought by reducing the risk of a financial crisis exceeds the welfare loss caused by rising output and inflation.

Macroprudential policies and tools are now being widely used by various central banks and financial authorities. However, many empirical studies have found that macroprudential policies for the housing market (especially LTV and DSTI limits, etc.) have a significant effect in slowing down the growth of bank credit, but the effect on stabilizing housing prices is not as significant as expected. In fact, these macroprudential measures are relatively moderate policies. If a gradual approach is adopted, the effect on housing prices is often even more unbearable. The Central Bank of Taiwan has implemented several waves of macroprudential measures since the end of 2020. However, as shown in Figure 3, the concentration of real estate loans has continued to rise, the trend of concentration of credit resources into the real estate industry has not stopped, and housing prices have risen sharply.

When financial stability is consistent with the overall objective of economic stability, tighter policy can cool the overheated housing market and prosperity, while stabilizing the financial sector and the overall economy. When financial stability conflicts with overall economic stability, the central bank must weigh the reduction of financial risks with the collateral damage on economic activities from monetary tightening; therefore, facing the threat of financial stability, LIW should not be ruled out. In-depth policy cost-benefit analysis is necessary for this question. Therefore, it should not be lightly asserted that interest rate policy is an overpowered and improper tool for the housing market.

Some recent studies have found that if monetary policy and macroprudential policy are aligned, better financial and overall economic stability may be achieved. For example, Nier and Kang (2016) found a strong complementarity between monetary and macroprudential policy. The use of the two policies together helps reduce systemic risk and stabilize macroeconomic variables compared to the use of one without the support of the other. The simulation results of Lambertini et al. (2013) show that when a macroprudential policy is used alone (upper LTV ratio limit), the volatility of the credit/GDP ratio is significantly reduced, but the volatility of housing prices is only slightly reduced. The use of monetary policy in parallel with macroprudential policy, when both policies are used in response to changes in credit growth, more effectively stabilizes output, credit and housing prices compared with the use of a single policy or other policy combinations, and achieves a higher level of social welfare. Current research on effective coordination between monetary and macroprudential policy remains highly divergent and needs further clarification.

Fulfilling its statutory responsibilities

This article has shown that major fluctuations in housing prices increase the volatility of the financial cycle, increase systemic risks, and threaten the stability of the financial system. Therefore, if the central bank is to fulfill its statutory duty of promoting financial stability, it must actively respond.

At the same time, low policy rates are one of the main reasons for rising housing prices, which has been confirmed by a large number of empirical studies. An active response will not only help maintain financial stability, but also assume the responsibilities of alleviating the negative effects of loose monetary policy on economic productivity and wealth distribution.

Finally, it is important to emphasize that the use of macroprudential policies alone has not been as effective as expected in curbing housing price rises and financial stability. Therefore, the role of rate policies should not be completely excluded from financial stability without in-depth research, especially in this long-term low-rate environment. In the face of various trade-offs, the most suitable policy combination should be pursued in response to housing price growth. The combined use of monetary and macroprudential policy is likely more effective in mitigating macroeconomic cycles. The central bank should review whether it has effectively used all possible policy tools. All parts of the government should share responsibility and carry out policy evaluation as soon as possible, and act promptly as necessary.