The content of this article represents the author’s personal opinions, and any errors are also the responsibility of the author.

Why should the central bank pay attention to housing price fluctuations? What is the relationship between that and the central bank's goals? Financial stability is one of the statutory goals of Taiwan’s central bank. Some people believe that housing prices are not the central bank’s focus; rather, it is concerned with financial stability. However, are housing prices unrelated to financial stability? The purpose of this article is to clarify this issue so that the central bank has a clearer position in response to rising housing prices. As far as the housing market is concerned, in addition to the growth rate of mortgage loans and their concentration – which are important financial stability indicators – since housing prices are a major part of the financial cycle, they are critical to financial stability. Moreover, the continued rise in prices will not only threaten stability, but may also lead to misallocation of resources, thereby reducing total factor productivity (TFP), and exacerbating the wealth gap, with destructive effects on financial, economic and social stability.

Meanwhile, the causal relationship between low interest rates and high housing prices have been established after an extensive number of empirical studies. The central bank may justify stabilization of this growth in housing prices in the following ways: (1) Reducing the threat to financial stability caused by loose monetary policy, and fulfilling its statutory responsibility to promote stability; (2) Reversing the negative effects of housing prices on productivity and wealth distribution caused by loose monetary policy.

Faced with trade-offs between different policy tools, the most suitable policy portfolio should be pursued in response to housing price increases, and the utility of interest rates should not be completely excluded. A combination of interest rates and macroprudential policies should be used, which should achieve better financial and overall economic stability than a single policy.

The link between interest rates and housing prices

In theory, an expansionary monetary policy with low interest rates can lead to higher housing prices through several transmission channels. (1) Ownership costs: When interest rates fall, owner costs decrease, and housing demand rises, leading to rising prices. (2) Anticipation of rising prices: Expansionary monetary policy creates expectations of rising housing prices, increasing current demand. (3) Credit channel: Expansionary monetary policy loosens household borrowing restrictions and increases housing loans and housing demand. (4) Risk-taking channel: Falling interest rates make investors more willing to take higher risks and switch to higher-risk investment targets, including real estate and mortgage-backed securities.

Because of the many factors in addition to interest rates that affect housing prices – including income, taxes, inflation expectations, population structure, and future price expectations – some studies show an insignificant impact of interest rates on housing prices. On the whole, however, the causal relationship between the two has been established after a large amount of empirical research: whether it is individual countries or cross-border data, recent decades or hundreds of years, advanced countries or emerging economies, various measurement methods, and methods to determine the exogeneity of monetary policy, have shown loose monetary policy (rates) is indeed one of the main reasons for rising housing prices. Therefore, the judgement that housing prices are related to rates should not be taken lightly.

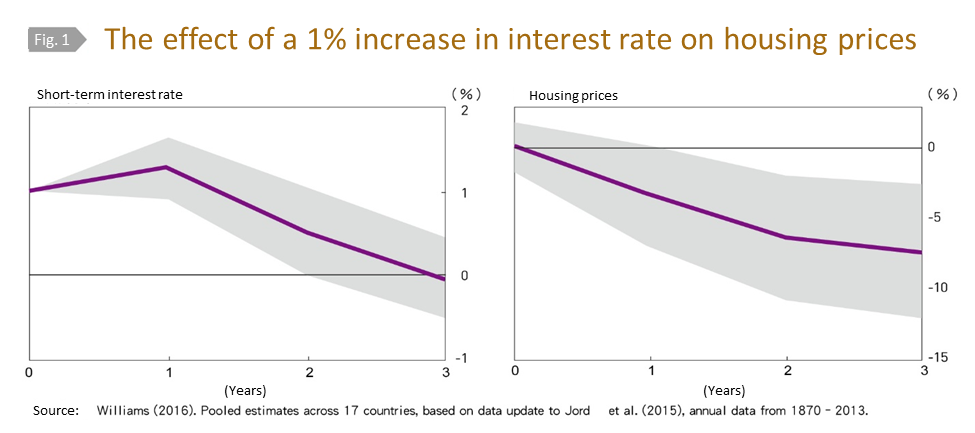

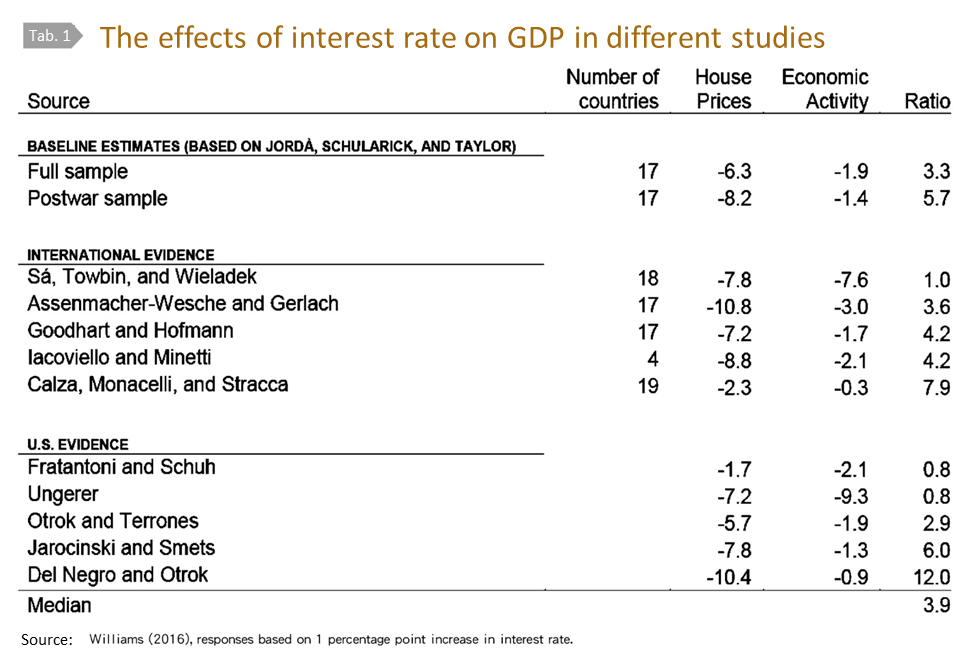

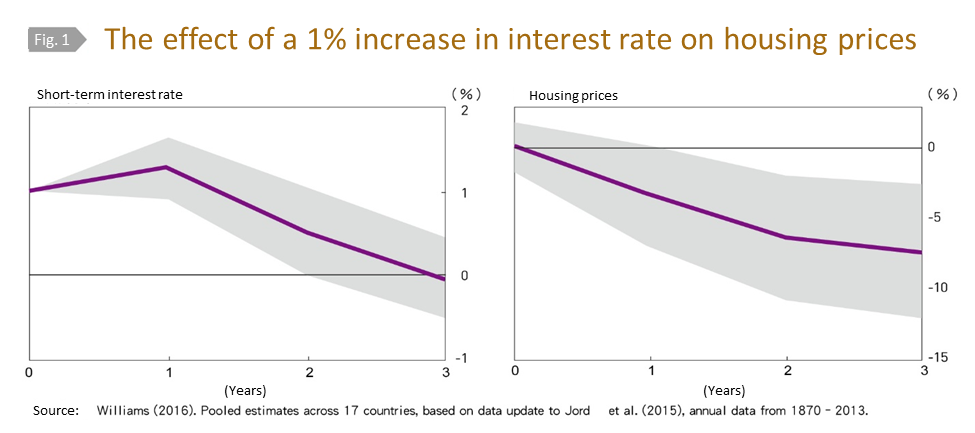

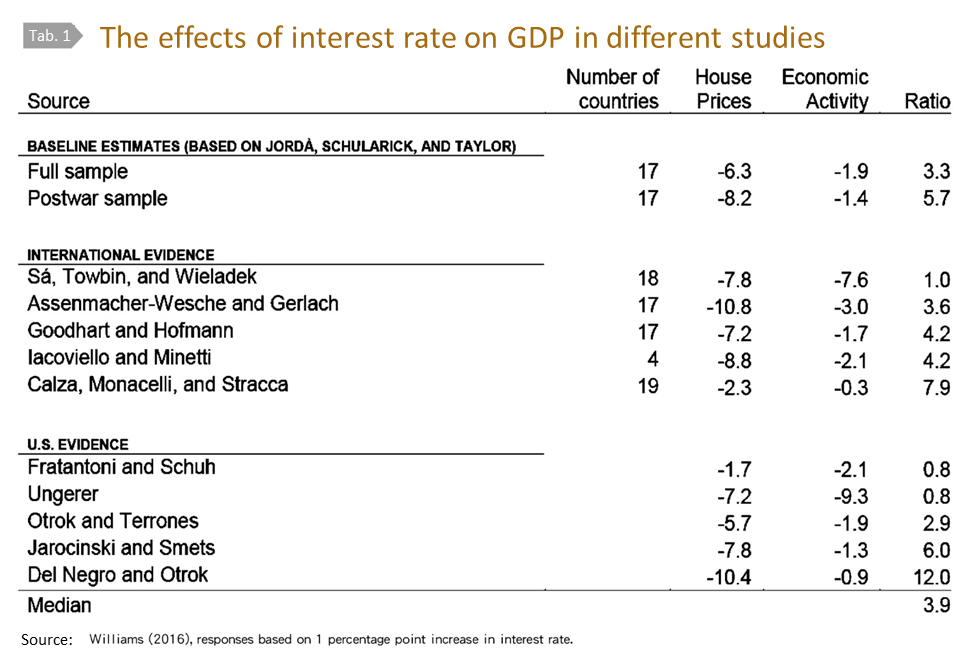

In Figure 1, Williams (2016) used annual cross-country data from 17 countries from 1870-2013. After excluding the endogeneity of monetary policy, the study found that the average impact of a 1% increase in interest rate on housing price is about 6.5%. Table 1 shows the impact of a 1 percentage point increase on housing from different studies (US and transnational data). The impact is about 3-6 times that on GDP; the median is about 4 times.

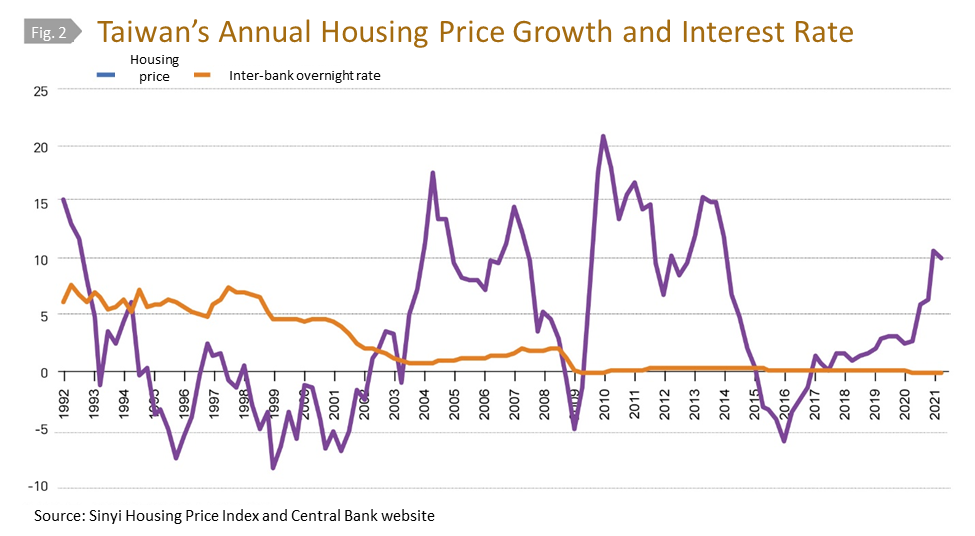

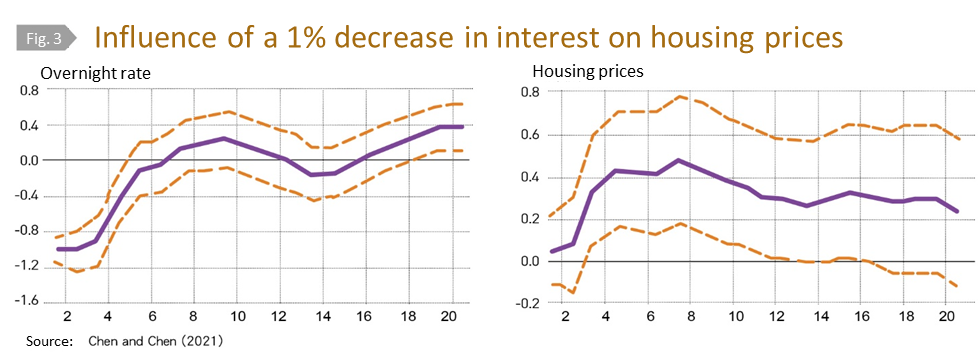

Figure 2 shows Taiwan's annual housing price growth rate against its interest rate since 1992. Preliminary examination shows that the correlation coefficient is -0.39 (from Q1 1992 - Q2 2021); of course, the relationship between the two needs to be confirmed by further quantitative analysis. Chen and Chen (2021) used Taiwanese data to build an SVAR model incorporating mortgage and housing market sentiment indicators, as shown in Figure 3, finding that changes in interest rates do significantly affect housing prices. When the rate falls by 1%, housing prices rise by 4.8%. The variance decomposition showed that interest rates explain 11%-14% of variation in house prices (in periods 12-20).

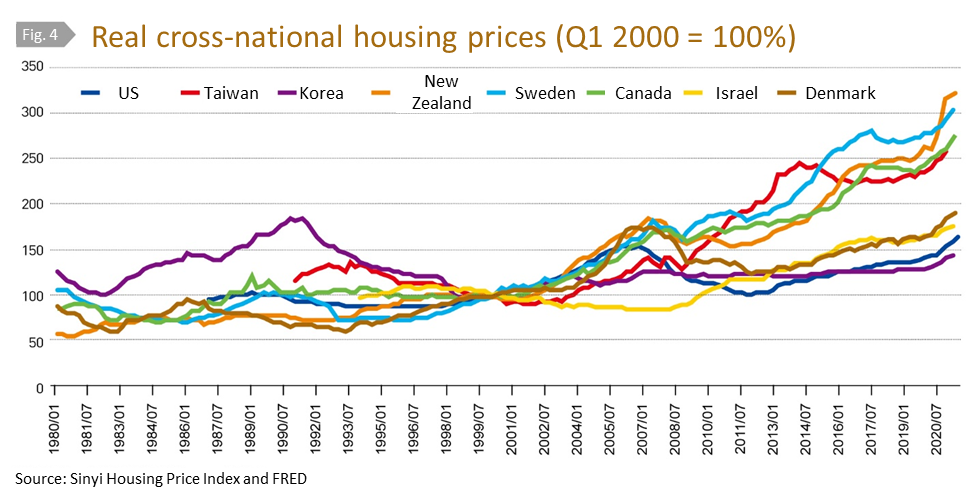

Since loose monetary policy is one of the main reasons for the increasing housing prices, are the past increases housing prices considered high? Recently, some have commented that the current housing price level and rises are still moderate. We can use the following indicators. One commonly used indicator is housing price affordability (including housing price-to-income ratio and mortgage burden ratio). Taiwan’s housing price-to-income ratio and mortgage burden ratio have been rising for a long time, from 4.5 times and 24% in 1Q 2002, respectively, to 9.1 times and 36% in 2Q 2021. Housing price affordability has shown a marked deterioration. In addition, one can also see the cumulative price increase. Figure 4 shows the historical trend of housing prices in Taiwan and some other countries, deflated by the country’s CPI into real housing prices. Using 1Q 2000 as the base period of 100%, Taiwan’s house prices in 3Q 2021 will reach 262%, and the cumulative real increase will exceed 160%. Comparing with other countries, the cumulative increase during this period is only lower than that of New Zealand and Sweden, where prices have soared recently, and comparable to Canada; but higher than most of the other countries (about 20 countries). For example, Korea, the US, Israel, and Denmark, etc., have recently experienced large increases, but the cumulative increases in Korea and the US over the past 20 years have only been 45% and 64%, respectively.