In recent years, extreme droughts and floods have become more frequent, and their intensity has increased. These weather events have not only caused loss of lives and property, but also endangered the long-term stability of the financial industry. Therefore, in 2020, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the world’s “central bank of central banks,” issued its Green Swan Report, explaining that climate change will become an important source of risks to global financial stability. In an attempt to reverse this situation, a Bloomberg article stated that many central banks and financial supervisors have become climate fighters.

Close relation to carbon reduction policies

Generally speaking, climate risk can be divided into physical impact and transition risks; its impact on industry credit risk is increasing. In the end, this risk will be transmitted and aggregated in the financial industry. Physical impacts, like extreme weather, cause loss of lives and property, leading to higher business costs and lower profits, which in turn increases defaults on loans. Transition risks, such as the implementation costs of carbon reduction policies to mitigate climate shocks, will affect the operation of carbon-intensive industries. If high-carbon-emission machinery and equipment are used as collateral in loan contracts, their value could collapse, which in turn would impact the financial industry.

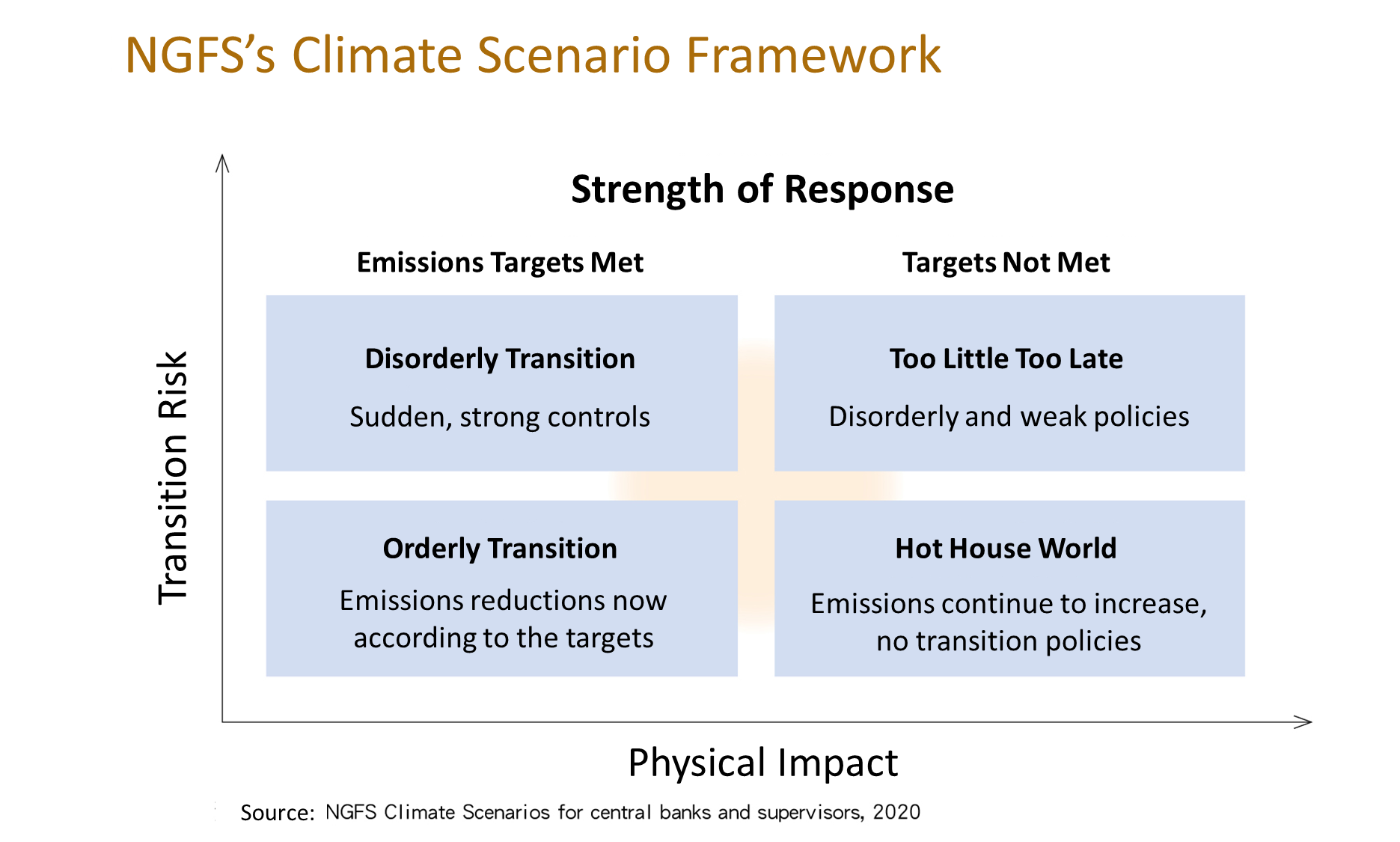

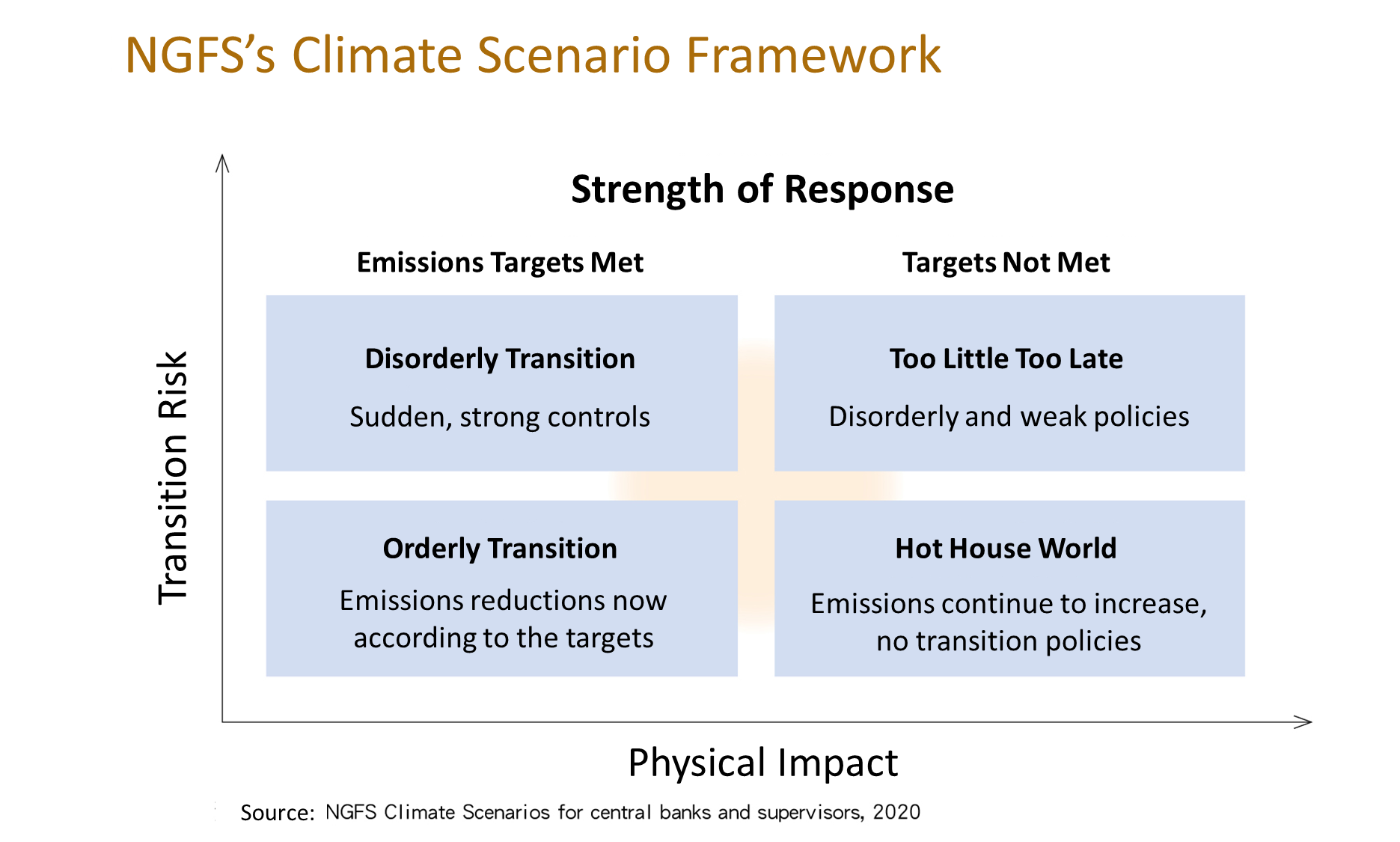

What are the possible scenarios for future climate risks? This is closely related to the ambition of carbon reduction policies. The Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) depicts the following three scenarios based on whether governments promote carbon reduction in a timely and orderly manner, and the response intensity. The X-axis in the figure represents the intensity of the policies, and whether they reach the reduction targets, which affects physical impact. The Y-axis indicates whether governments promote these policies in a timely and orderly manner, which affects the transition risks.

Orderly transition

In this scenario, carbon is actively reduced now to more effectively control both physical impact and transition risks. If net zero is reached before 2070, there is a 67% chance that the temperature increase will be kept within 2°C. If net zero is reached by 2050, there is a 67% chance of keeping the increase within 1.5°C.

Disorderly transition

In this case, the carbon reduction is too slow. Global emissions will not peak until after 2030, before finally accelerating carbon reduction; alternatively, carbon reduction efforts will be focused on certain countries or industries. Although net zero is finally achieved, the risk of this disorderly transition will be higher than that of an orderly transformation, and the process more painful.

Hot house world

By maintaining the current inadequate carbon reduction policies or simply implementing the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) of the Paris Agreement, although there is less transition risk, the physical impact will increase due to inadequate reduction. Global greenhouse gas emissions will continue to increase until 2080, and the earth will warm by 3°C, causing irreversible sea level rise.

Transition risk forecasts

The NGFS model forecasts that if reduction policies are promoted in an orderly manner, the transition cost will be much lower than with disorderly transformation. The cumulative impact on GDP of a disorderly transformation by 2100 would be over 9% of GDP, but with an orderly transition, the impact would drop to 4%.

Physical impact forecasts

NGFS reported that in a hot house world, the cumulative reduction in GDP from physical impact will reach 25% by 2100. In addition, many physical risks could not be included in the assessment. For example, their model did not include regional conflicts caused by refugee migration or losses from sea level rise or natural disasters.

The report also showed that if the temperature rises by 1.5°C, the annual probability of extreme heat waves is about 3%, and about 9% in tropical regions; when it rises by 3°C, the probability is about 17%, and about 42% in tropical regions. 20% of the population is exposed to this risk. Furthermore, when the temperature increases by 3°C, the sea level will be 50-80 cm higher in 2100 than in 2005, and in 2300 by 140-250 cm. In addition, the impacts of global warming on food production will vary greatly. Some regions may be slightly positively impacted, but some will be negatively impacted, and the impact on tropical regions will be particularly significant. If the temperature increases by 2°C, wheat production in the tropics may be reduced by 20%.

Challenges come from opportunities

A report by the European Central Bank (ECB) asserted that government green transition policies and measures will increase the probability of corporate defaults, but the medium- and long-term benefits will be the reduction of physical risks and stimulation of sustainable innovation, both of which will be greater than the previous costs of carbon reduction. Thus, these policies have long-term payoffs.

The implementation cost of green carbon reductions in the context of a disorderly transition would be higher than in an orderly transition, although these costs would be lower than the physical impact of more frequent natural disasters under uncontrolled warming. In that context, the physical impact would exceed the cost of orderly transformation. In other words, the increase in losses or insurance premiums would erode that low-cost basis.

The ECB predicts that in the disorderly transition or hot house world scenarios, the mining industry would have the largest increase in credit risk over the next 30 years. The median default rate in the industry would increase by about 1.1%, and the default rate of the worst 5% would increase by 1.7%. Mining is followed by the power and transportation industries. The report also found that the vulnerability of individual companies to physical impact varies greatly, by nearly four times, and is particularly high in certain regions.

In 2021, MSCI will assess the transition impacts on different industries in different situations. For example, when the temperature increase is kept within 1.5°C, the transition impact on carbon-intensive industries is relatively high. European energy companies will decrease in value by 67% on average, but in the same period, innovative low-carbon technology will also grow in revenue by 18%. Power companies would lose nearly 60% in asset value, but carbon transformation will also increase the industry’s revenue by 40%.

However, if the temperature increases by 3°C, this means that the carbon reduction policies of various governments are more passive, and the transition will impact the value of many assets. Power companies will decrease in value by about 20%, but at the same time, innovation and technology will bring new ideas. Revenue will also be substantially reduced, due to insufficient incentives for carbon reduction. That is to say, transition costs and physical risks are often at both ends of the same seesaw. Unwillingness to actively reduce carbon emissions in order to avoid transition costs results in more physical risks.

Physical risks are greater than transition costs

In September, the ECB issued its first climate stress test report. Its methodology assessed the transition costs and physical risks, and how they influence profitability, leverage, and credit risk. The simulation showed that if global warming is not controlled by 2050, corporate profits will be reduced by 40% compared to the orderly transition, and the median corporate default rate will also be 7% higher than during the orderly transition. During an orderly transformation, however, because of the high carbon price or other reduction measures, credit risk will increase slightly at first; yet in the long run, the benefits will be sufficient to offset the short-term costs. That is, the impact of physical risks will be highly significant, because the increase in intensity and frequency of climate-related disasters will increase property insurance premiums, which in turn increases operating costs and affects corporate revenue. In addition, natural disasters cause asset losses, triggering new investment demand, which in turn increases leverage.

In fact, financial climate stress tests are an extension of KYC. Financial institutions must be able to understand the possibility of asset or collateral losses under extreme weather conditions. For example, a Bank of England report found that about 10% of mortgages in the UK are in flood-prone areas. Therefore, it is recommended that banks check how much mortgage collateral is located in flood-prone areas, and then estimate the resulting losses based on flood heights. Bank of America (BOA) used a Category 5 hurricane to simulate the possible loss of its real estate collateral. According to the flooding risk in the AR5 scenario of the “Ministry of Science and Technology Disaster Management Information Research and Development Application Platform,” a domestic financial holding company found that 7,148 of its loans are in high-risk areas, involving NT$ 27.8 billion in collateral, equivalent to 3.39% of its overall guarantee credit. Another financial holding company found that if the temperature increases by 3°C, its mortgage loss rate will increase by about 3 basis points.

In addition, banks must also bear the costs of transition. For example, increases in energy taxes and other measures to increase carbon pricing are likely to reduce the revenues of high-carbon companies and even affect their ability to repay loans. Citibank stated in its 2020 TCFD report that a carbon price of US$ 50 per ton would downgrade the average credit rating of oil companies by 3.5 points. A domestic financial controller estimated that if the government sets a carbon price of US$ 50-100 per ton of emissions from the petrochemical industry, its costs would increase by about 0.75% by 2030. Coupled with a lack of water, its revenue would decrease by 1.36%, causing 96 of its 662 petrochemical customers to decline in credit rating one grade, and four to decline two grades. The average default rate would increase by 0.5bp. Another financial holding company expects to lose about 7-18 basis points in its lending to the steel industry.

The BIS report concluded that the next systemic financial risk may be caused by climate shocks, so financial supervisors have the responsibility to prevent such a result. In other words, they must use their supervision tools to require financial institutions to assess and calculate their climate risks and exposure. This is also why the FSC issued the Green Finance Action Plan 2.0 in 2020, strengthening disclosure of climate risks, and also allowing companies to follow suit and be optimally prepared for the impact of climate change.

Su Han-pang is the director of the Third Research Institute of the Taiwan Research Institute, and Chen Honda is Senior Researcher at the Taiwan Institute of Banking and Finance.